First published by Xinhua| 2024-06-13

MUTOKO, Zimbabwe, June 12 (Xinhua) — With utmost pride, Marova Moyo admired the lush green butter beans in her garden in Mutoko, a district in Mashonaland East Province of Zimbabwe.

For the 62-year-old farmer, nothing is as therapeutic as witnessing the legumes flourish under her care.

Despite the El Nino-induced drought facing Zimbabwe, Moyo and her husband, Abel Katsande, still harvested enough grains to last them until the next harvest, thanks to climate-smart farming practices that ensure the sustainable use of land and resources.

After noticing declining harvests due to deteriorating soil quality, Moyo adopted conservation farming, a climate-smart method in which farmers dig holes to use as planting basins that retain moisture, allowing crops to thrive even with limited water.

“We realized that it’s the only way to ensure that we preserve the soil, protect our health, and conserve the environment at the same time getting high yields,” said Moyo in a recent interview with Xinhua.

The conservation farming concept involves minimum soil disturbance, crop rotation, and the use of mulch. Mulch helps conserve moisture and suppress weeds, while manure improves soil structure.

“The advantage is that on a small portion, you can harvest enough to sustain your family and sell the surplus,” said Moyo.

Moyo is a member of the Zimbabwe Smallholder Organic Farmers Forum (ZIMSOFF), an organization that envisions improved livelihoods of organized and empowered smallholder farmers practicing sustainable and ecological agriculture.

Ever since she adopted conservation farming on a one-and-half-acre (about 0.61 hectares) piece of land, the yields have more than doubled. The practice has also helped her commercialize farming.

Moyo expressed her belief that the key to her success is adhering to the principles of agroecology, a sustainable farming way that works with nature. “Every part of the ecosystem has a role to play,” she said.

The mango tree in her garden, for example, provides fruit to her family, and the surplus goes to the market. The leaves it sheds provide mulch, and the pruning provides firewood. When she gets tired, she rests under the shade. The tree also helps prevent erosion and provides a shield against wind.

All she does in return is to water the tree.

When crops are harvested, nothing is discarded. “Everything is recycled here. Even the maize stalks, we use them as mulch, some as livestock feed. Goat and chicken droppings are used as manure,” Moyo said.

Agroecology plays an important role in promoting sustainable farming, said Patience Shumba, program officer for the ZIMSOFF. “In the face of climate change, agroecology offers a holistic and integrated approach that can protect, restore, and improve agriculture and food systems,” said Shumba.

While many families will need food aid this year, Moyo’s small portion provided enough for her family.

“People now realize that even if there is a drought, I won’t sleep on an empty stomach. If there’s no rain, I still harvest. So many people are now coming to learn how I do it,” she said.

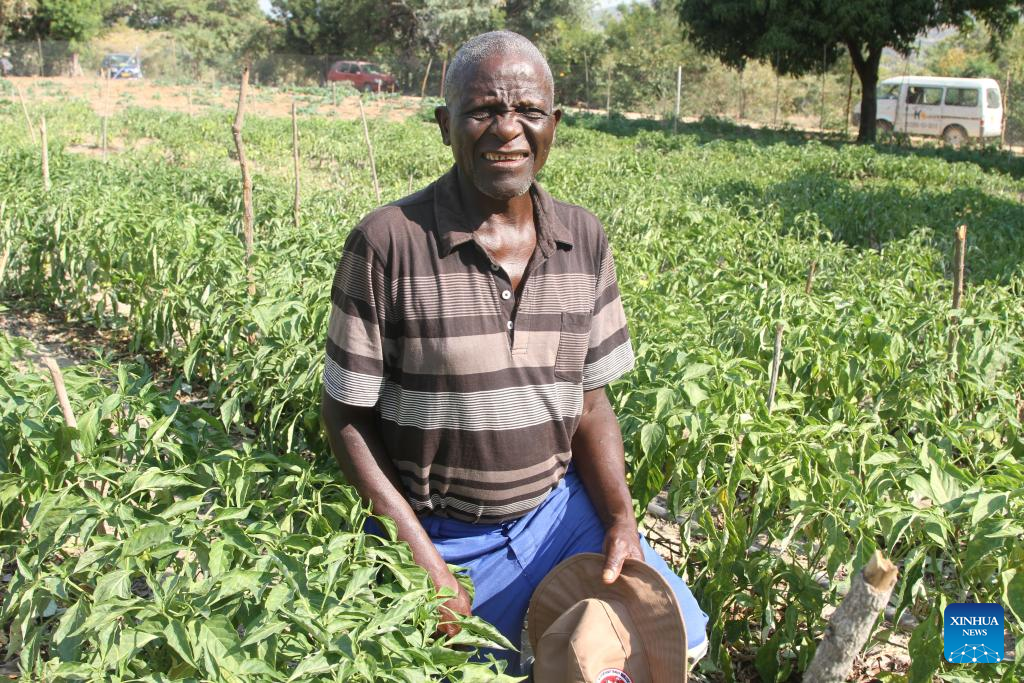

A few kilometers from Moyo’s field, Kahukwa Kanyonganise constructed a water-harvesting system that collects runoff water from nearby rocky mountains and channels it into a reservoir beneath them. The water is used to irrigate his crops.

“This region does not receive enough rainfall, so I decided to harvest the water so that I can preserve the little we get,” the 73-year-old said, adding that his water-harvesting initiative enables him to grow maize, the staple crop, out of season.

In Zimbabwe, maize is grown by small-scale rural farmers mainly through rain-fed agriculture, leaving them at the mercy of the increasingly unpredictable natural environment.

Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa in April declared a state of disaster over the El Nino-induced drought that left maize crops in many parts of the country as a write-off.

About 9 million people, more than half the population, will need food aid until March next year, according to the government. ■